Disability in Mythology

Key Takeaways about Disability Representation in Early Mythology

- Disability is a common theme in mythologies across cultures, often represented by gods and heroes

- Hephaestus, the disabled Greek god of blacksmiths and artisans, is a prominent example of disability representation in mythology

- Mythological narratives often reflect and shape cultural perceptions and attitudes towards disability

- Examining disability in mythology through a critical disability studies lens reveals problematic tropes like the “super crip” and disability as divine punishment

- Modern interpretations and retellings of myths are an opportunity to challenge stereotypes and promote more nuanced, empowering disability representation

Why study disability in mythology?

Mythology has long been a powerful medium for exploring the human experience, including the lived realities of disability. Disabled gods, heroes, and figures feature prominently in the mythologies of many cultures, reflecting and shaping societal perceptions of disability.

By examining these mythological representations through the lens of critical disability studies, we can gain insight into the historical and cultural contexts that have influenced attitudes towards disability, and identify opportunities for more inclusive, empowering narratives.

Disability in Greek Mythology

An image of Hephaestus, the Greek god of fire, blacksmiths, craftsmen, and volcanoes, portrayed in an early 20th-century esoteric art style. This depiction should blend ancient Greek mythology with the mystical and arcane aesthetics characteristic of esoteric artwork from the early 1900s

Greek mythology is a rich source of disability representation, with the god Hephaestus being perhaps the most well-known example. Son of Zeus and Hera, Hephaestus was the god of blacksmiths, artisans, sculptors, metallurgy, fire and volcanoes. He is described as being born with a disability – either a congenital impairment or as a result of being thrown from Olympus by his mother Hera.

Despite his disability, Hephaestus was a skilled craftsman and integral part of the pantheon. He created many of the gods’ iconic accessories, including Zeus’ thunderbolts and Athena’s shield. In some versions of his myth, he uses a wheeled chair or chariot to move around, demonstrating his ingenuity in adapting to his impairment.

An image of the blind prophet Tiresias in an early 20th-century esoteric art style. Tiresias is depicted as a wise, elderly figure with his eyes covered, symbolizing his blindness.

Other disabled figures in Greek mythology include the blind prophet Tiresias, who was compensated with prophetic abilities, and the centaur Chiron, a revered teacher who suffered from an unhealable wound. These myths raise questions about disability as a divine punishment or “trade-off” for extraordinary gifts.

Chiron the centaur is shown holding ancient scrolls or a book, symbolizing his wisdom and status as a mentor to many heroes. An unhealable wound is visible on his side, a poignant detail highlighting his vulnerability and the source of his deep knowledge of healing.

Disability in Norse Mythology

In Norse mythology, the god Odin is a complex figure associated with war, wisdom, and poetry. According to legend, Odin sacrificed an eye in exchange for a drink from the well of wisdom. This “divine impairment” and its association with knowledge challenges the notion of disability as a weakness.

Odin, the one-eyed Norse god, stands contemplatively by the Well of Wisdom, his sacrifice for unparalleled knowledge etched in his powerful stance amidst the Yggdrasil tree and ancient runes, rendered in dark mystical hues with golden accents

Another prominent example is the god Tyr, who lost a hand to the monstrous wolf Fenrir. Tyr’s sacrifice is portrayed as an act of bravery and a symbol of honour, suggesting that disability could be acquired in service of a greater good in Norse culture.

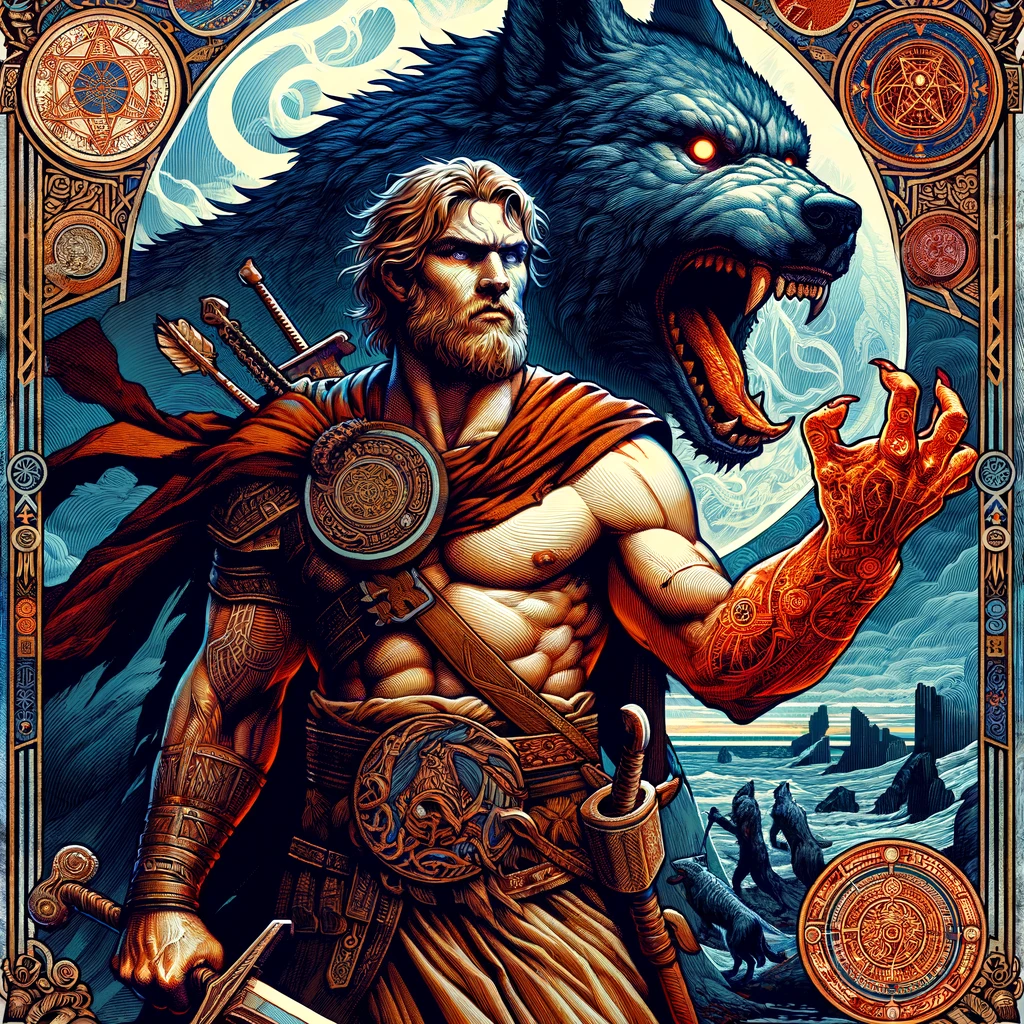

Tyr, who lost a hand to the monstrous wolf Fenrir, depicted in an early 20th-century esoteric art style

Disability in Hindu Mythology

Hindu mythology also features disabled gods and figures, such as Ashtavakra, a sage who was born with eight physical deformities. Ashtavakra’s story subverts expectations by presenting him as a spiritual authority and intellectual equal to able-bodied scholars.

In the Hindu epic Mahabharata, Dhritarashtra, the blind king of Hastinapur, is a central character. Though his blindness impacts his ability to rule, the narrative explores the nuances of his experience and relationships rather than reducing him to a one-dimensional trope.

The Role and Perception of Disability in Mythology

Across cultures, mythological representations of disability serve various symbolic and narrative functions. Disabilities are often used as a sign of divine disfavor or punishment, as in the Christian characterization of the Greek god Hephaestus as a “fallen” figure akin to Lucifer. Alternatively, a god’s impairment may be compensated with supernatural gifts, such as Tiresias’ prophetic abilities or Odin’s wisdom.

Disability is also frequently deployed as a plot device or source of conflict. The disabled god or hero must overcome challenges related to their impairment to prove their worth and be accepted by their able-bodied peers. This “super crip” trope, while ostensibly empowering, can promote unrealistic expectations and erase the everyday realities of disability.

Mythological narratives also explore the intersections of disability with other aspects of identity, such as gender and sexuality. Hephaestus’ disabled masculinity is a source of mockery from the other gods, and his marriage to Aphrodite is portrayed as non-normative. These myths reflect and reinforce cultural stigmas around disability and desirability.

Modern Interpretations and Influence

Contemporary adaptations and retellings of mythological stories have the potential to perpetuate or challenge traditional disability stereotypes. Rick Riordan’s popular Percy Jackson series, for example, features Hephaestus as a character but does not deeply engage with his disability identity.

In contrast, some modern interpretations use mythology as a vehicle for exploring disability experiences and promoting positive representation. Neil Gaiman’s novel Norse Mythology humanizes the disabled god Tyr and portrays his impairment matter-of-factly. The Disability in Kidlit website features reviews and discussions of disability representation in children’s and young adult literature, including mythological retellings.

Disability activists and scholars are also drawing on mythological figures to celebrate disability identity and challenge ableist narratives. The Disability Visibility Project, founded by Alice Wong, aims to amplify disabled voices and foster community through storytelling. By reclaiming and reimagining mythological characters like Hephaestus, disabled people are asserting their place in the cultural imagination.

Conclusion

Disability is a significant theme in mythologies around the world, reflecting the ways in which different cultures have historically perceived and constructed disability. While many traditional mythological narratives perpetuate problematic disability stereotypes, they also offer opportunities for subversion, reclamation, and the creation of new, more inclusive stories.

By applying a critical disability studies framework to the analysis of mythological representations of disability, we can better understand the cultural roots of ableism and work towards more authentic, empowering portrayals of disability in contemporary media and storytelling. As disabled people continue to reclaim mythological figures and forge their own narratives, we can look forward to a richer, more diverse disability mythology for the modern age.